Step Three: Entry Sheet & Creative Activity Introduction (エントリーシートと創造的活動紹介)

The entry sheet was the first actual hurdle to clear. The entry sheet is a phenomenon unique to Japan in how ubiquitous and incredibly comprehensive it is. Pretty much every single company in Japan uses this when hiring university graduates, and it is way more detailed than the kind of CV/Résumé required by any company this side of the planet. This was also the point where I had to commit to applying for a planning role, which prevented me from applying to any other role (one application a year is the rule).

While pre-entry was geared towards obtaining basic information about you (contact details, etc.), the entry sheet, as a souped-up résumé, requires you to write in detail about everything of note you have done. First up was an exhaustive list of my hobbies and interests, what kind of media I enjoy, and what I got up to at school and university in terms of extra-curricular activities.

Next up was a section asking if I had lived abroad anywhere, and if so, for how long. Of course I entered my time in the UAE and UK. I also had a chance here to list what languages I can speak. I think this shows that they are aiming to incorporate people into their staff that have a wider range of experiences and pools of knowledge to draw from, which is always a good thing in game design.

Following this, there were several pages of questions that required written answers, each with a maximum limit of characters – at most 200, and at least 100. Some of the questions were more generic, such as “Concretely describe your major and what your topic of research is”, “What type of person would you say you are?”, “What attracted you to apply to Nintendo?” and “What do you think production planning entails?” – questions where you talked about how you could apply what you already know at the company. But, there were some more Nintendo-ish questions in there too, like “What kind of games do you like/have an emotional attachment to?”. I remember writing in Minecraft and Europa Universalis IV, as well as a couple more “Japanese” games to balance out the mix.

One that took me a while to think over was “What do you normally value most in your ‘craftsmanship’?” due to its use of the Japanese phrase “Monozukuri” (ものづくり). I also had to write a short summary of my years at Elementary School, Middle School and High School. The last question on the form asked me what kind of things I would want to tackle/challenge if/when I join the company. I wrote that I wanted to leverage my experiences growing up in the Middle East to help the company expand in the MENA region with the hope of offering Arabic localisations of Nintendo products.

In addition to the entry sheet, those applying to be a planner (and design roles I’m guessing too) had to fill in a “Creative Activities Introduction Form”, where you picked the three most important creative projects that you have worked on, and introduced them, explained how you approached the project and what you learned from it all. You also had to attach a PDF for each entry. I chose to talk about my BAFTA Award nomination first (because that seems to impress everyone I bring it up to), my YouTube channel second with a one-page fact-sheet I wrote up, as well as my font design work with a portfolio in the form of a short sample e-book.

In total you had about a month to get these documents submitted. But, if you wanted more time, there were several of these application periods for each position spread throughout the first half of the year, so you could temporarily save your forms and submit them in one of the other periods, as long as they were both sent at the same time.

Step Four: Test (筆記試験)

It was roughly a month after I submitted that I received an email with the results of my entry sheet. I did not expect it to pass, but it in fact did, much to my surprise. It left me with a lasting feeling of validation, and hope that I might actually get to an interview. After you pass the Entry Sheet, the process seems to open up a little more, and Nintendo provides you with some information about working for the company as a new recruit, and what it’s like to live in Kyoto. Like many Japanese companies, they provide support for your first couple years of work in the form of rent subsidies and other benefits. Though you start with a lower salary, you end up saving more – seems good. But standing in the way of such a job was the most difficult part of any shuukatsu application: the test.

Each company approaches this stage differently, but in general, Japanese companies employ something called the “SPI Test” (適性検査) or “Suitability test”. Normally these tests include sections that test maths, English, as well as Japanese. Nintendo seems to have originally carried out two stages of tests – one online and one on-site. But either due to internal reforms or the virus situation, the two have now been rolled into one online test. I already knew that Nintendo did things a little differently by employing a version of the test that was unique to them, and one that was much harder. Taking the advice that Heristyo wrote, I started doing SPI practice questions for the three supposed sections of the exam, though I figured that I would probably score zero on the maths section as I can barely do mathematics in English, let alone Japanese. I had some hope that I could scrape by on the Japanese sections and of course sail through the English.

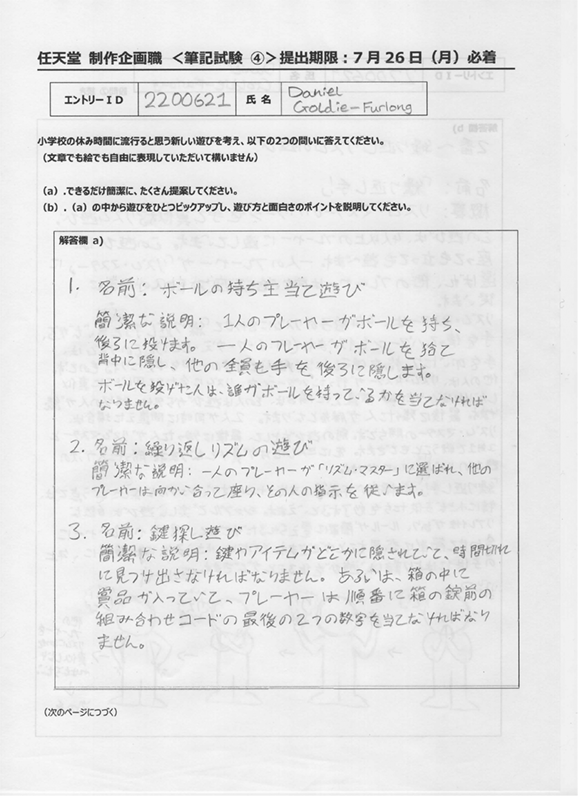

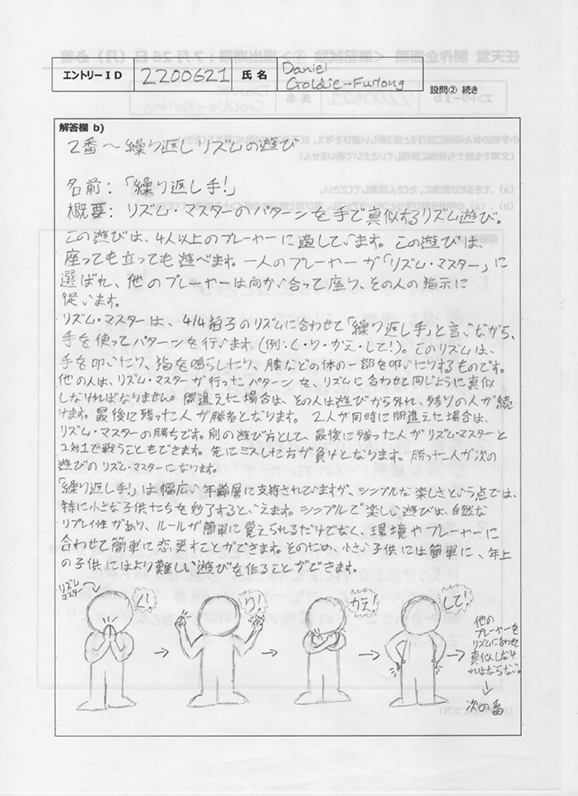

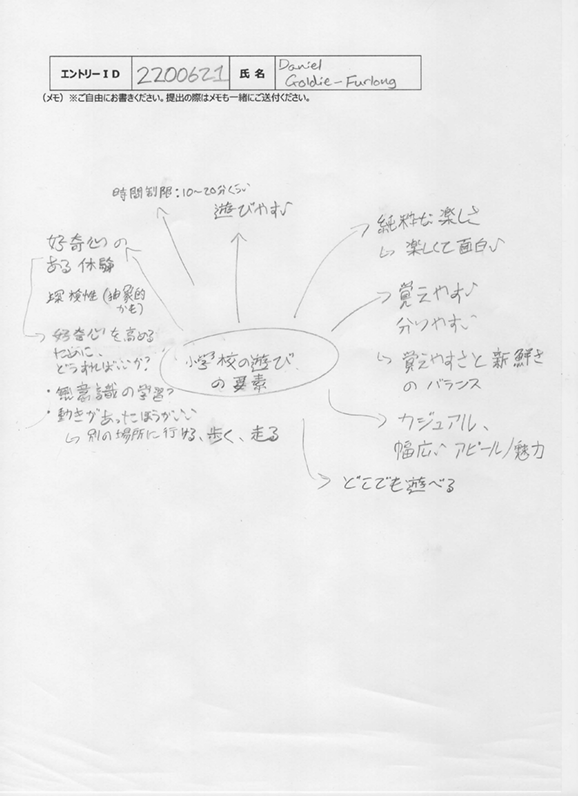

The first thing to tackle however was a supplementary test that was given to planning applicants to complete in their own time over the course of a week, to hand in on the day of the online test. For this I had to print out three sheets and fill them in by hand, to then scan and submit them to Nintendo. Presumably the briefs change each year, but the general idea was that you are given a creative brief, and have to come up with ideas before choosing one to run with and flesh it out on the other side of the page. I was asked to “Think of a new game that you think would be popular during elementary school recess”. Underneath I had to brainstorm as many ideas as possible before picking one up to flesh out. This was tough.

Apart from recalling my own experiences as a kid, I spoke with some Japanese and other Westerners to try and get an idea of what people liked to play at that age. I did some research into different playground games to see what I could put a spin on, or perhaps see if I could mesh together ideas from different places around the world. In the end, I came up with an idea for a rhythm game which was probably not all that original, but I had my Japanese proofread so that it would at least be understandable. I imagine a significant part of this test was making sure you could communicate your ideas effectively, as well as see what you came up with.

Like the seminar, the online test was scheduled for the afternoon – which meant another early start for me. It is somewhat known that Nintendo, as one of the more popular companies for applications, receives tens of thousands for graduate positions every year, which means that most of those who submit entry sheets have to be eliminated from the race. In total there were just over a dozen of us candidates in the test Zoom call, one of a couple different meetings scheduled for the production planning candidates. We were all instructed by the disembodied voice of the recruitment manager to make our surnames and candidate numbers our meeting names, as well as turn on our webcams so that we could be monitored. It turned out that with my suit and a tie, I was one of the more formally dressed people there – most decided to forego wearing a tie or a suit jacket. All of the candidates were men, and I was the only person present who was not Japanese. Pretty sure there were some stares of curiosity when I switched on my camera.

But I at least felt somewhat ready to deal with the standard SPI fare, until Nintendo threw a curve-ball at me…